Signpost at the US-Mexican border. (Chess Ocampo/Shutterstock)

The late ’60s revolutionized the United States—and my dad.

In the wake of the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, and with increasing political unrest in Mexico City, my dad was scheming his own revolution. He wanted to live the American Dream.

For a young man from a small Mexican coastal village, building a better life for himself and his family in a new country felt nearly impossible. But several decades (and jobs) later, my dad and mom have done just that. Somehow through all of the crap they’ve endured, they were able to construct their version of the American Dream.

My own dream is to follow in their footsteps, but in reverse: like my parents, I want dual citizenship in both countries eventually, but move from the US to Mexico. My older brother has already relocated to Mexico from California, and my sister has also obtained Mexican citizenship.

That plan is growing among US citizens. A key motivation is that the American Dream—the idea that working hard, attending college, buying a home, and choosing when and how to start a family—is faltering. The land of opportunity ceases to exist.

Surviving in America means enduring a chaotic world filled with soaring housing and health care costs, a tanking educational system, devastating gun violence, and surging racism.

During Donald Trump’s first presidential term, my dad said that if he were a young man living in Mexico in the current climate, he would not venture into the US. “It’s not worth it,” he said at the time. And it’s only gotten worse in Trump’s second term.

“It’s like being in a toxic relationship,” Vannessa Vasquez said of life in the US. “You shouldn’t be anywhere where you don’t feel comfortable or where you feel like they don’t have your back.”

Vasquez, an actress documenting her relocation to Mexico, is working on getting her Mexican citizenship. And she’s not alone. In the past 15 years, there has been a notable increase in Mexican Americans gaining citizenship (and/or moving) to Mexico. In 2016, the Mexican government even launched a campaign called “Soy México,” which aimed to reach more people who wanted to become Mexican citizens.

Vasquez says she feels at peace living in Mexico City. “Perhaps because these are my people. I don’t feel scared.”

Living across two cultures is second nature for Mexican Americans, but it is also a complex experience. There’s a storied and infuriating saying among our community (37.2 million Mexican Americans living in the US) that we are “ni de aquí, ni de allá,” which translates to “we are not from the US or Mexico.”

However, as more Mexican Americans seek to reclaim identities and cultures in both countries, the idea of genuinely being from here and there is increasingly possible.

Finding hope beyond US borders

Nicole Macias, a writer from Los Angeles, obtained Mexican dual citizenship last year. She plans to relocate to Mexico eventually to escape the US and, more importantly, to thrive in the future in the motherland.

But what does that future look like? Pretty good. It’s no secret that Mexico’s health care system is very affordable and accessible. Mexico is also providing plenty of job opportunities for both Americans and those recently deported. The cost of living in Mexico is sharply lower than in the US. Additionally, purchasing a home is significantly less expensive and easier if you’re a Mexican citizen.

“I’m single,” Macias said. “I don’t have any kids, and there’s still no way I could ever afford to purchase a home in Los Angeles.”

She added, “One thing my siblings and I had always talked about was potentially buying property for our parents to retire. I feel like [getting dual citizenship] was the right step to do. And also, the state of the nation right now is really insane.”

Getting Mexican citizenship can be arduous, as I learned when my sister went through the process. The Mexican government and various online tutorials provide information on all the required documents.

Macias diligently researched the best way to get her dual citizenship and ultimately settled on contacting Doble Nacionalidad Express, a legal firm specializing in helping individuals obtain dual citizenship between the United States and Mexico, and submitted her paperwork for $350.

From writers to athletes, a shared desire to honor family history and reclaim agency is guiding this dual-citizenship movement.

Former Minor League Baseball player Rafael Arroyo, also known as “Rox,” initially traveled back and forth to Mexico for work as a baseball player developer. He traveled so often that someone suggested he obtain citizenship to avoid the long lines at the airport.

“It means the world to me,” Arroyo said of the flexibility of having dual citizenship. “I understand what my family went through. My grandfather was a bracero, and my father came to the US and worked as a cook for forty-plus years, working two jobs and buying a home. All of that hard work didn’t go to waste. I was able to take advantage of their sacrifices, the purpose of which was to give their children more opportunities. So that passport signifies generations of blood, sweat, and tears.”

The new migration: Older Mexican Americans seek roots in the motherland

Dr. Claudia Masferrer, co-author of “The Mexican Dream: Studies on US Migration” and a professor at Centro de Estudios Demográficos, Urbanos y Ambientales de El Colegio de México, has been studying the growing population of Mexican Americans in Mexico. She said that this population was initially younger.

Between 2000 and 2015, the population of American minors living in Mexico more than doubled. By 2015, nearly half a million minors born in the US lived south of the border.

Newer studies indicate that this population is trending older due to an increase in first-generation Mexican Americans seeking to relocate to Mexico. There are several factors contributing to this trend. For starters, while online chatter suggested that people (mostly celebrities) threatened to leave the country after Trump was elected, it was more during the COVID pandemic that people began to relocate, as they could work remotely.

More recently, however, as the accessibility of gaining citizenship in Mexico became more apparent, especially on social media, 37.2 million Latinos of Mexican origin who live in the United States as of 2021, according to a Pew Research Center, have the opportunity to live and travel more easily between Mexico and the US.

In 2023, approximately 35,000 US-born Latinos registered to become Mexican citizens, with about 40% being 21 years or older.

That community fascinates me—older Mexican Americans yearning to go to the land of their ancestors. Take, for example, Doris Anahi Muñoz, an artist from Southeast Los Angeles who said she fantasized about one day living in Mexico.

“Ever since I was a little girl, I dreamt of moving here,” Muñoz said. She moved to Mexico City two years ago after becoming a dual citizen.

While many Latinos I interviewed said they felt a sense of liberation from having dual citizenship in Mexico and the United States, Muñoz said she had survivor’s guilt. Ten years ago, her brother was deported from the US, and he remained in Tijuana, just across the border from San Diego, to stay as close as possible to his family. Muñoz became emotional as she recalled the first time she visited her brother in Tijuana and the moment when he had to exit her vehicle so she could cross back into the US.

“It just broke my heart,” Muñoz said. “It made me so angry. Why can I go back to our family, and he can’t?”

Muñoz said that feeling of guilt continued to haunt her when she realized she would be leaving behind all of the activism for immigrants she participated in back home in the US.

“A lot of the work I used to do was being in the trenches, working on immigrant rights organizations, so now being here in Mexico, it does feel like survivor’s guilt because I am not in la lucha on that side. I am not in the streets protesting like I used to be,” Muñoz said.

Muñoz added that she realized she had experienced burnout from her work as an activist during her 20s. Now that she’s in her 30s, a friend suggested that she change her perspective on her situation as an American living in Mexico and see how she could still be of service in her new home.

But living in a new country, despite being a descendant of that country, isn’t an easy transition. Muñoz describes residing in Mexico City as a place of healing but adds that it’s a double-edged sword.

The otherness that Latinos face in the US—not being American enough—exists in Mexico as well. Muñoz experienced that firsthand when a Mexican kid noticed her Spanish accent and asked her where she was from. Due to the increase in gentrification, particularly in Mexico City, she felt compelled to share her entire background story with the child to explain why she was in Mexico in the first place. The kid said, “‘Oh, you’re a gringa,’” to which Muñoz responded, “Don’t call me that.” “I’m not a gringa in the US, so please don’t call me that.”

So the notion of neither being American enough nor Mexican enough continues to plague this group of Latinos.

Despite some judgment from locals, Mexican Americans living in Mexico are bonding and building a stronger, more united community. Muñoz said she’s intentionally sought out people with the same experience.

“There’s a very specific connection that happens among Chicanos,” Muñoz said, “That’s why Chicano culture exists, right? Feeling ostracized in the US, and creating that subculture in order to feel like we belong somewhere. So when I see Chicanos in Mexico, I get so happy because they want to connect to their roots.”

This story originally published on COURIER.

Senator Catherine Cortez Masto leads effort recognizing Hispanic Heritage Month

The Senate passed a bipartisan resolution celebrating Latino cultural and economic contributions, uplifting the 68 million Hispanics in the US, who...

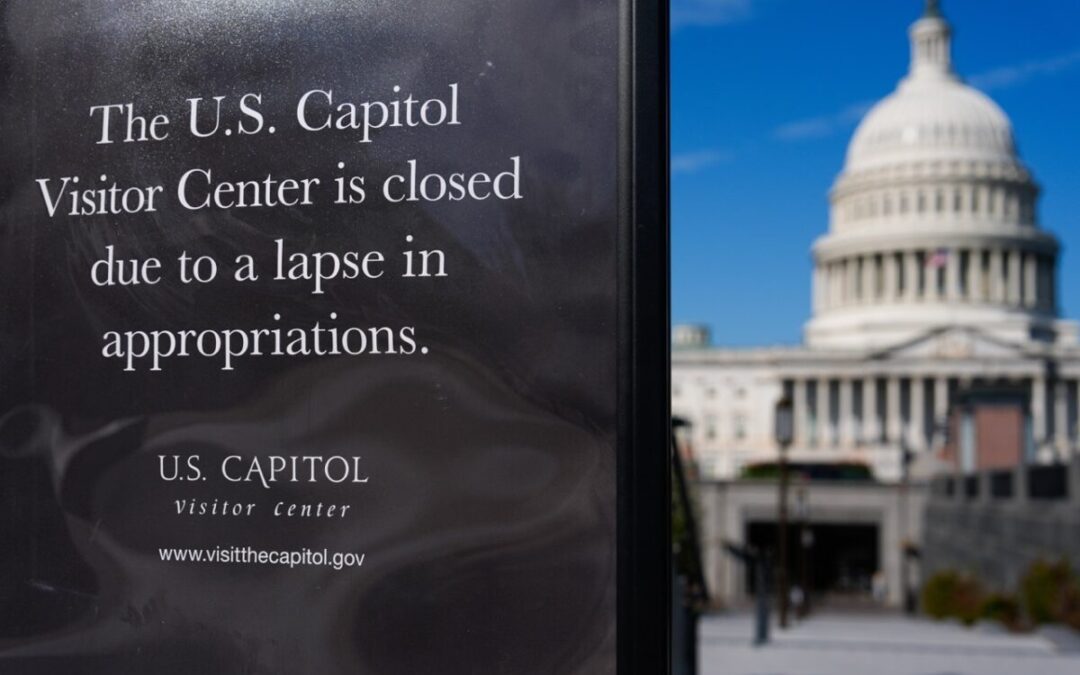

4 claves para entender qué significa el cierre del gobierno y sus consecuencias

Si sólo tienes unos segundos, lee estas líneas: El Congreso de los Estados Unidos no aprobó una ley de financiamiento a corto plazo (conocida como...

‘Sick to my stomach’: Trump distorts facts on autism, tylenol, and vaccines, scientists say

By Amy Maxmen Originally published September 22, 2025 Ann Bauer, a researcher who studies Tylenol and autism, felt queasy with anxiety in the weeks...

What would a government shutdown mean for Nevada?

As a federal shutdown looms, Congressional Democrats hold out for a better deal for their constituents. The federal government could soon shut down...

Conservative activist Charlie Kirk dies after being shot at Utah college event

OREM, Utah (AP) — Charlie Kirk, a conservative activist and close ally of President Donald Trump, was shot and killed Wednesday at a Utah college...

Nevada Democrat cautions against war in Iran

Assemblyman and veteran Reuben D’Silva believes diplomacy can keep Iranian nuclear threats at bay. Nevada Democratic Assemblyman Reuben D’Silva...