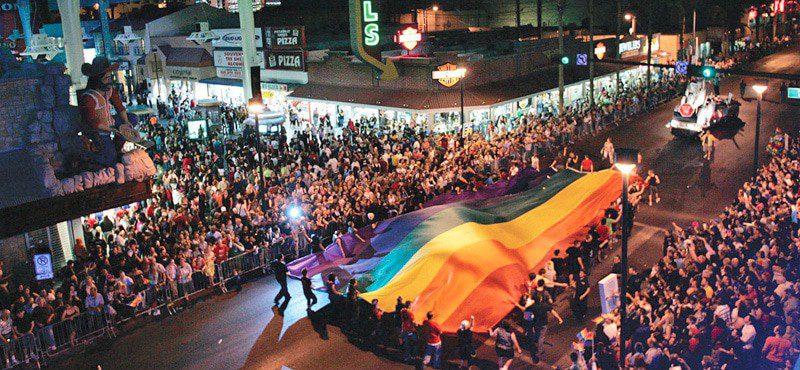

Pride parade on April 25, 1998. (Dennis McBride/University of Nevada, Las Vegas Special Collections and Archives)

Dennis McBride remembers the thrill of coming out in 1970s Las Vegas.

“What was it like as a newly minted queer in Las Vegas in say 1975? It was something that was naughty, and being naughty was good,” said McBride, a historian and author of “Out of the Neon Closet,” a book about Nevada’s LGBTQ+ history.

From Reno drag performers who hid in clubs in the 1930s to Las Vegas’ first official gay bar in 1972 to Nevada’s first openly gay elected official, David Parks, taking office in 1996—Nevada’s LGBTQ+ elders have seen a lifetime of change, resilience, and survival.

For decades, stories of LGBTQ+ pioneers who shaped Nevada’s cultural landscape have been passed down quietly through word of mouth. Now, community groups and historians like McBride are committing those stories to history with oral projects and archives.

But that doesn’t mean queer visibility isn’t an issue today. These elders are still facing challenges—health care discrimination, housing insecurity, and isolation.

“Sometimes when every legal recourse you have has been taken from you, all you can do is just the testament of your living.” McBride said.

What came before

(Dennis McBride/University of Nevada, Las Vegas Special Collections and Archives)

In 1914, former Nevada Supreme Court Justice Patrick McCarren expanded the state’s 1861 sodomy law, calling homosexuality “an act against all laws of nature.”

When Nevada emerged as a destination for tourism, hospitality, and entertainment in the 1930s, LGBTQ+ representation also took hold with The Cowshed, a lively nightclub in Reno that featured “The World’s Foremost Female Impersonator,” Belle Livingstone. Livingstone moved to Reno from New York City and opened The Cowshed, where they hosted drag performances until 1937.

Many of the state’s first and iconic gay bars started to open up between the 50s and 70s—from Maxine’s in Las Vegas in 1950 to the 1099 Club in Reno and Le Cafe in Las Vegas in 1970. These were not just nightlife spots; they were community spaces. But safety wasn’t guaranteed. The clubs were hotspots for police raids.

“The [Las Vegas] Metropolitan Police Department would cruise around the gay bars in their police cars, taking down license plates,” said McBride, who experienced this first-hand. “Occasionally they would raid the bars and would line everyone against the wall, and make all the lights come on and check your ID.”

‘Charged’ out of the closet

Dennis McBride outside of his home in Las Vegas, NV.

When McBride was growing up, records of who identified as LGBTQ+ weren’t readily available. Many in the community were hiding out of fear. But he was also growing up in the time of hippies, cultural changes, and the Civil Rights Movement.

McBride said he experienced his own change at the age of 5.

“I used to read comic books. We used to call them ‘the funnies,’ and in the back there were all these bodybuilding advertisements for Charles Atlas. I remember lingering over them, but not thinking about it till much later,” he said.

It wasn’t until his early adulthood that he started to realize what his sexuality was. Like for so many queer youths during his time and even today, it was life-changing but also terrifying, he said.

“I was really shaken with that, because all I knew was that to be queer, was to be sick and rejected,” McBride said.

As a former University of Nevada, Las Vegas student, he recalls going to therapy after a sexual experience with a man and being told that it was OK that he didn’t like it.

“All he had to say was ‘It’s OK. You know, you didn’t have to like it. Doesn’t mean you’re not [gay],’ and that’s all I needed. Was just to be told by someone else that it’s OK,” McBride said. “I charged out of my closet like the roadrunner and never looked back.”

Jerry Cade, an old friend of McBride whose own queer story is chronicled in “Out of the Neon Closet,” grew up in a small, conservative Texas town. Today, Cade is a medical director in Southern Nevada. From across the table, while speaking with the Nevadan, he laughs while remembering how he never had a “coming-out” phase.

“When I figured out I was gay at 19, I told everyone,” said Cade. “I never went through a closeted phase. August 16 or 17, 1974, I told everyone. By August 19, I had my first boyfriend.”

Barriers that remain

(Dennis McBride/University of Nevada, Las Vegas Special Collections and Archives)

The fear of being unsafe isn’t uncommon among queer elders. A national survey by the Center for Healthcare Strategies found that 77% of LGBTQ+ adults believe residents in a senior home will not socialize with an openly out resident. Another 89% fear being discriminated against by staff.

This stigma pushes many LGBTQ+ seniors into hiding in care settings. Others avoid them entirely. André Wade, state director of Silver State Equality—which brings the voices of LGBTQ+ people and allies to institutions of power in Nevada and across the United States, said many seniors may also choose to live with family or friends instead, while others continue working past retirement age due to the rising cost of senior housing.

According to the American Heart Association, when it comes to health care for seniors, the fear of isolation is so strong that some families who receive at-home health care “de-gay” their homes by removing anything related to being queer or involving their identity.

This happens despite legal protections in Nevada against discrimination based on a person’s sexual orientation.

‘Be very vigilant right now’

(Dennis McBride/University of Nevada, Las Vegas Special Collections and Archives)

Despite a lifetime of challenges and entering a new phase of life with its own vulnerabilities, community leaders still hold hope that they can give LGBTQ+ seniors the quality of life they deserve.

“If we’re lucky and blessed, we will one day become older and want resources and care for ourselves. It’s important to create the resources and care for them now,” said Wade. “I’m hopeful that we will also be able to capture some of the rich history and experiences of these individuals who have seen a lot, and have done a lot in the movement. There are lots of stories there to learn from.”

Meanwhile, Nevada historian McBride is shouting his story for as long as he can and calling on the next generation to do the same.

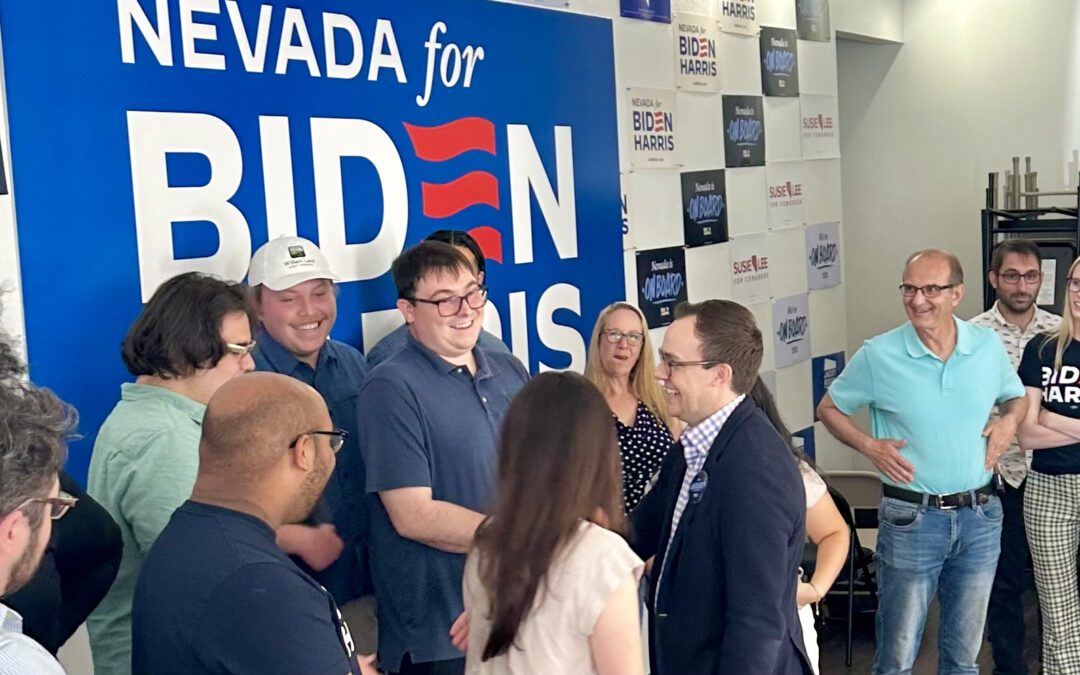

“Nevada queers need to be very vigilant right now. They need to pay attention to what’s happening locally and federally,” McBride said. “You’ve got to keep yourself well informed and involve yourself politically. Going to rallies and protests and running in government can help.”

Opinion: LGBTQ seniors deserve to age with dignity. Addressing housing issues can help.

This article was first published by Las Vegas Sun. By 2030, the population of LGBTQ+ adults over age 50 in the US is expected to reach 7 million....

Opinión: El Mes del Orgullo significa celebrar la diversidad y el empoderamiento LGBTQ+

Junio marca el Mes del Orgullo, un momento dedicado a honrar a la comunidad LGBTQ+ y celebrar su historia, logros y contribuciones a la sociedad. El...

Opinion: Pride Month means celebrating diversity and LGBTQ+ empowerment

June marks Pride Month, a time dedicated to honoring the LGBTQ+ community and celebrating their history, achievements, and contributions to society....

Celebrate Pride Month with these must-read books

We asked our colleagues across Courier Newsroom to share recommendations for books by LGBTQ+ authors. Here’s what they said. Reading allows us to...

Opinion: Silver State Equality is Getting Out the Vote

This Piece was previously published in the Las Vegas Pride Magazine; click on this link to read their publication. History will remember...

Chasten Buttigieg: LGBTQ rights could be at stake in November election

In a Q&A, the husband of Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg tells The Nevadan that, when it comes to LGBTQ issues, the difference between...